To You I Surrender My Vanity @ Suma Orientalis

The Christian ring to the exhibition title is deliberate – Eng Hwee Chu’s devotion to her religion and family, are clearly on display in her art. Consisting of signature acrylic paintings, preparatory sketches, watercolours & pastels, and charcoal & graphite drawings, this collection of works provides a satisfying look-through at the 50-years old’s career. Entering the new bungalow-cum-gallery space, the visitor is greeted by two paintings from the “Black Moon” series made in the early 1990s. The crimson figure and its corresponding shadow, wavy landscape as background, gestures of anguish and cynicism, are all hallmarks in Hwee Chu’s subsequent output. Her more recent works on display suggest an increasingly confident and still-evolving artist.

|

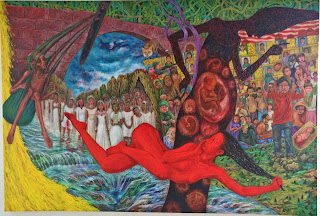

| Victims of Struggling Live (2017) |

The exhibition statement describes well a typical painting by Hwee Chu – “(s)he casts her doppelgänger self and others close to her into her paintings, lingering them onto the canvas surround, as symbols around the messages she is eager to propound.” A cursory glance at her oeuvre, and it is apparent turmoil and strife are the precepts postulated; Hwee Chu’s paintings recall murals of the Christian Judgement Day and the Buddhist Hell, its self-contained images arranged in overlapping axes on the flat picture plane, levelling too any sense of a fixed sequence. The artist’s usage of background tropes can be tedious – a horizon that ends with the sky, dense forest or sterile ground, memorial portraits or cultural motifs, swirling water and gushing gold shower – yet the careful inclusion of each component contributes significantly to her works’ emotional impact.

|

| After Lost (2013) |

The number of figures featured in Hwee Chu’s pictures, have increased as compared to her earlier works, and are progressively depicted in more detail. Ever-present are the burning nude self and her darkened & textured companion, while representations of babies and children, an imagined public, and spectral beings, now become vital symbols. In ‘Authorities Behind Women’, some figures are elongated à la El Greco, the bodies twisted to form an elliptical space enclosing a persecution scene underneath a streetlight and a curving stone arch. Balancing the shape on the left is another ellipse, a misshapen stadium with a façade of arcades, in which a blindfolded cleric assumes an accusing pose. One pink lying nude, a flying horse toy, and the gesturing shadow, anchor the swirling picture, while a luscious flow of gold hold together its elements. The composition is forcefully dynamic, yet brazenly attractive.

|

| Authorities Behind Women (2016) |

Such arrangements of pictorial subjects to create movement, is surprisingly less effective in Hwee Chu’s vertical paintings. Scale dissimilarity among narrow environs in ‘After Lost’, results in a close-packed image of desolateness like a compressed triptych, its floating orb-tombs appearing neither in or out of the picture. In ‘Silent Cry’, one argues that the children at the painting’s bottom is intentionally positioned out-of-focus as such; However, the different brush strokes Hwee Chu apply in blue to create visual continuity is counterproductive. I attribute the relatively successful ‘Return Home’ to its static dimension and clear horizon, with figures entering/existing the picture denoting an expanded picture plane. The positions of the ladies kneeling on the bottom left, and its alignment to other figurative gestures within the painting, testifies to the artist’s mastery at compositional balance.

|

| Return Home (2012) |

The virtuosity on display in ‘Origin of Women’ is breathtakingly superb. Portals are utilized cleverly to depict many dimensions, while just a few figures define the swirling movement that Hwee Chu’s paintings typically project. Two lingam-shaped archways roughly frame the expansive picture, while a tiny wooden cross hanging above a patch of green grass, marks the centre. Metaphorical symbols represent beauty and suffering, while life and death is clearly illustrated as intertwined states, as I stare at a baby bump next to one deceased visage. The interplay of gestures (and cultural stereotypes by skin colour) between men and women occur in a shallow pool, while a dimly-portrayed lady covers her ears. Women come into being if they fulfil gender role standards; It is wise to turn a deaf ear to this echo chamber.

|

| Origin of Women (2013) |

Social expectations, then, is the main subject matter in Hwee Chu’s paintings. The struggle (as a filial daughter, an obedient wife, a life-giving mother, etc.) has always been a personal one, but as her self-realization grows, her art simultaneously matures by drawing in external elements that define one’s gender role. These are not feminist images that stir awareness towards gender equality, but a lament of one patriarchal reality. As compared to the sparsely-composed “Black Moon” paintings, the newer works enthral via more complex renderings (and interpretations) befitting the topic at hand. With hymns humming in my ears, I finally see these works as devotional paintings – grounded observations cloaked in symbols, that happen to be situated within surreal landscapes. The self is surrendered, in honour of a greater truth.

|

| Silent Cry (2016) |

““When the unclean spirit has gone out of a person, it wanders through waterless regions looking for a resting place, but not finding any, it says, ‘I will return to my house from which I came.’ When it comes, it finds it swept and put in order. Then it goes and brings seven other spirits more evil than itself, and they enter and live there; and the last state of that person is worse than the first. While he was saying this, a woman in the crowd raised her voice and said to him, “Blessed is the womb that bore you and the breasts that nursed you!” But he said, “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and obey it!””

- Luke 11:24-28, New Revised Standard Version

|

| Women, Life Warrior (2015) |

Comments

Post a Comment